REPORT. Resistance Movement activist Marcus Hansson has been living in a military tent for the past three months. In this personal article, he tells us about his experiences and shares a few tips with readers.

Why have I lived in a military tent for three months?

I think the answer to this question will be the most important thing I write in this article. When I was in jail, I got a lot of writing done. I had plenty of accumulated ideas in my head that I wanted to commit to paper, and all kinds of distractions were denied to me – something that isn’t always negative, as I got so much work done because of it.

During the autumn I continued working on all my articles, one of which turned out to be “Material wealth enslaves you”. In this article I used a picture of an old man living in a tent out in the wilderness to get my point across. After this, I played with the idea of what it would be like to live in a tent, just like that old man. If he could do it, so could I. This was one of the reasons – trying to live where you have no access to everyday equipment.

Having said that, I didn’t plan for very long. After making my decision, it only took about two weeks for me to set up my tent in the woods. I’m a very spontaneous and adventurous person, but until now my adventures have usually involved modern comforts such as hotel rooms, taxi trips and being close to civilisation. Although it’s fun to be spontaneous, it’s still a character trait that causes certain inconveniences, which I will elaborate on later in this article. In order for spontaneity not to become too problematic, a large degree of flexibility is also required, otherwise things can easily go wrong. Doing something spontaneous and adventurous was therefore one of the reasons for this venture.

Another factor was that I’m from Scania, in the southern part of Sweden. I grew up in an apartment where it was so hot (except when the electrical bills ran too high) that you could walk around in your underwear pretty much all year round. I have since adopted this behaviour as an adult (or perhaps I always had it in me genetically) to the degree that I feel most comfortable in an indoor environment where you practically start sweating in just your underclothes. I also sleep best in a large bed where I can stretch out like a cat. This has always hampered my sleep during wilderness activities with my Nest comrades, as I have been forced to sleep in a sleeping bag on top of a hard sleeping mat. Therefore, daring to break my comfort level was another reason.

One more reason – and the one I regard as the most important – is that I’ve done this to test myself, but also because I’m hoping to inspire other people from the Nordic race to have the courage to test themselves. It does not necessarily have to entail camping out in the woods, but rather gaining enough self-awareness to understand where your weaknesses lie as an individual, and to have the courage to improve yourself in these areas, no matter how hard or unfeasible it may seem. This is an attitude that Thomas Sewell talked about in his interview with Nordic Frontier.

My goals

I wanted to live out in nature, but I didn’t want to cut myself off from daily life, my duties in the organisation or things that could help simplify my camping experience. I’m no wilderness expert when it comes to constructing a windshield or campfire-building and so forth. I have taken the opportunity to refill my water supply at gas stations, shower in other people’s homes, and do my laundry and recharge my electrical equipment when needed. I have deliberately had access to the internet in order to be accessible, perform certain tasks and use it as a support tool. For the sake of simplicity, I thought I would list the goals I set for myself:

- To see if I could recreate a prison-like environment in which I could read a lot of books and write articles about them.

- To teach myself how to use water straight from nature in order to cook food on the stove, wash my clothes and myself.

- To be able to handle the cold when I have to sleep in minus-degree temperatures in a sleeping bag on top of a sleeping mat and camping bed.

- To sleep on my back, take baths in cold water and manage my tent and all the other equipment in winter conditions.

- To perform this feat north of the southern part of Scania, in order to do it in minus-degree weather.

- To do it for longer than one month in a row.

How it’s been going

Because things happened spontaneously, I ran into some problems, as I hadn’t actually scouted out a good spot. Since I needed to park my car without having to shovel snow for 200 metres every time I had to take a trip in it, it turned out that potential parking spaces were quite limited for me during the winter months. This meant I had to find a place in the woods of southern Halland about 700 metres away from my parked car. Consequently, I had to wade through knee-deep snow for the first few days, which really took a toll on me. This could have been avoided had I planned things much earlier. When all the snow melted later in December, it turned out that I had put my tent up beside a small forest path. I chatted with a few people following this path, even though I preferred to remain as undisturbed as possible. Not having anyone else close by has been nice.

The second issue was firewood. I didn’t know how much firewood would be needed, and thanks to Sweden’s environmental policies, people basically buy up all the firewood to avoid sky-high electricity bills. Finding firewood in my immediate area thus turned out to be somewhat of a problem – something that could have been avoided had I planned things better. As a side note, I’ve consumed five cubic metres of chopped firewood in the last three months. I haven’t burned any on some days, never at night, and only for half the day when I’ve worked out. I have spent 3,100 SEK on firewood, which I probably could have gotten a lot cheaper had I bought it in time.

The weather

Winter is a much kinder season in the southern parts of our country. This fact has suited me well, as otherwise things might have gotten too much for me. According to the Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute (SMHI), December was colder than normal, with a mean temperature in my location of -1⁰C. In Umeå, the mean temperature was reportedly -5⁰C. Around Christmas it was so cold here that the trees started snapping. At night the temperature reached -15⁰C, but I still managed to sleep. In January I moved to Blekinge for a change of surroundings, and the weather was milder than usual. As I’m writing this, the SMHI has not yet commissioned a report for February, but I’ve hardly encountered any minus-degree temperatures this whole month and the temperature has stayed around 3⁰C.

Equipment

I have done most of my laundry by washing it in soap in a 15-litre packing bag. The only hurdle was washing a large towel. A tub was much better suited to this purpose.

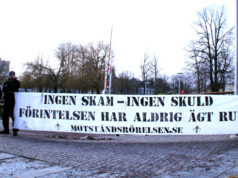

The only time I didn’t sleep in my tent these past three months was when it would have unnecessarily complicated things when the Nordic Resistance Movement went to Stockholm to demonstrate against vaccine passports. Then I did spend two nights sleeping on a couch. For some reason that is still not 100 percent clear to me, I’ve had to get up at night to urinate. I’m suspecting the cold weather was the reason for it, because I didn’t need to do it when I slept on the couch, or now when the weather is warmer. Or could it be because I can handle the cold weather better now?

Winter bathing

The amount of clothes I’ve had to wear to feel warm while asleep has decreased drastically. In the beginning I wore two pairs of long johns, a thick sweater, two pairs of knee socks and two hats. Now I’m down to just one pair of long johns and one hat, and occasionally my two pairs of socks. I’m able to handle the winter bathing much better now. Before, I would get terribly cold and had to put on a lot of clothes as soon as I entered the tent. Now I can take my time and dress in my underclothes without having to put on any more clothes inside the tent.

In December I lay down in rushing water when I took my winter baths in minus-degree temperatures. For two minutes I lay there until I lost sensation in my hands and feet. It felt as if my feet had fallen asleep when I walked across the rocks, and my towel and sponge felt like they were tearing my skin apart. Since I mostly bathe to keep clean, I have not attempted to increase the time I spend in the water.

The tent has held out really well this winter. Apart from having to hammer down the tent pegs when it was extra windy, and clean out the tent chimney, there haven’t been any problems. There haven’t been any issues with the food either, as I’ve mostly cooked stews in a large pressure cooker. These were easy to heat up with some basic foods such as rice, pasta and potatoes. Although I’ve simplified most of my cooking in the form of larger stews, I have still managed to cook beef bourguignon and fry a porchetta on the stove. Today I’m attempting a bouillabaisse (French fish stew).

Something I haven’t managed to do is sleep on my back, and it has been more uncomfortable to sleep on my side because my equipment is not designed for it. I’ve been sleeping longer hours than usual due to fatigue. I guess it makes you feel more worn out living like this. It has not been unusual for me to lie on the camp bed for ten hours. On the other hand, my sleeping has improved with time, but my brain is still not firing on all cylinders, which forced me to abandon the idea of reading books and writing articles when I moved to Blekinge in January. My main goal changed to working out, and I’ve been really good at that. I’ve been hiking a lot with my backpack on; running; and, when my feet were tired, I went swimming in a bathhouse. So I’ve been training hard several days a week, except for the days when I was sick.

Having a man cold is tough in itself, but having one in a tent while low on firewood is even worse, as it forced me to decrease the number of fires I could light when I was ill. Luckily, the temperature hovered around 4-6⁰C, which meant it wasn’t too cold if I stayed in my sleeping bag.

Overall, I’m happy with what I have achieved so far. I’ve gained a lot of experience during this time. Another important thing is that I’ve survived the winter in a tent, and I would be able to do it again. This means that if the authorities decided to increase their harassment against me, I would be able to head off and live in a tent in the southern reaches of our country, even in winter. As long as I’ve got my tent, firewood, sleeping mats and a good sleeping bag, I can do it. Everything else I need can usually be found in the home or can be bought for a cheap price.

The government must now be prepared to rob me of a military tent and fireplace in order to really test me. It’s not enough to evict me from a house, apartment or caravan. In such a case, I would simply take my tent and head for the woods.

But this doesn’t mean I’m done yet. In the coming months, I’m planning to live in a smaller tent without a stove. I’ve already begun to prepare.